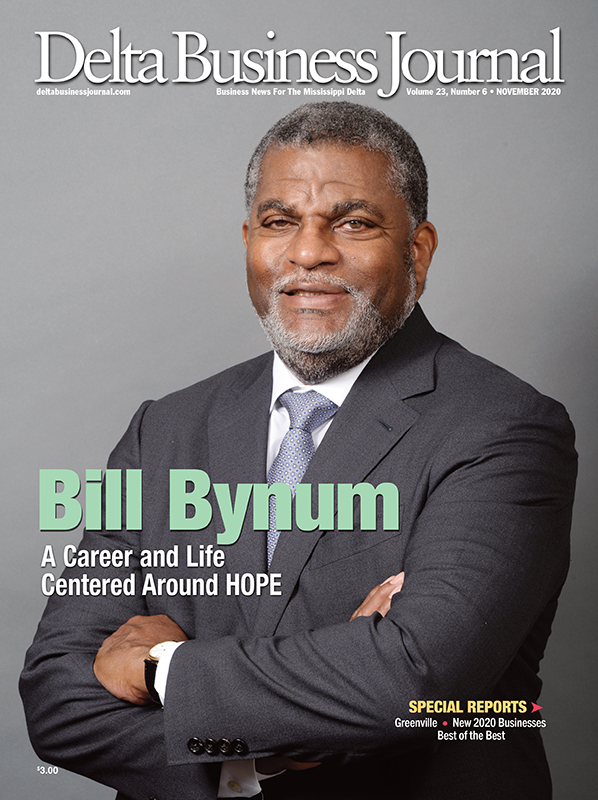

A Career and Life Centered Around Hope

By Jack Criss • Photography by Greg Campbell

Bill Bynum has done a lot of good in his career. As CEO of HOPE (Hope Enterprise Corporation, Hope Credit Union and Hope Policy Institute) based in Jackson, MS, Bynum and his team, as stated on the organization’s website, “provides financial services; aggregates resources; and engages in advocacy to mitigate the extent to which factors such as race, gender, birthplace and wealth limit one’s ability to prosper. Since 1994, HOPE has generated more than $2.5 billion in financing that has benefitted more than 1.5 million.”

Perhaps lost in those impressive financial numbers are the thousands of individuals and businesses Bynum has “done a lot of good” for—and that is what drives the man.

Born in East Harlem in New York City, his parents having moved to the city from North Carolina, Bynum lived there until the first grade when his family decided to return to the state. “We moved back to North Carolina just outside of Chapel Hill to an old mill town actually named after my ancestors who had once worked there as slaves. In fact, Bynum was home to one of the largest cotton mills in the country until the 1970s when it ceased operation,” says Bynum.

Bynum stayed in the Chapel Hill area after graduating high school, attending the University of North Carolina (at the same time a young man named Michael Jordan was on campus), where he initially planned on studying journalism. “I loved writing at the time and still do,” he says. “But, I got pulled into student government and ended up with a double major in political science and psychology. From there, in the mid-80s, I was on my way to law school, but got sidetracked into going to work with an organization that helped people who were losing their jobs due to outsourcing and cheap labor abroad. I was brought into this organization to explain and teach what worker ownership was, as its main goal was to act as a worker’s co-op, and to get their feedback, as well. I got hooked. It was great to help many of their workers buy the companies they had worked for, help them restructure them and, essentially, save their jobs.

“I think we’re products of our environments and I was just led to do this kind of work, which is helping people in need or who need assistance in addressing issues that came about through no fault of their own. When I moved back to North Carolina, there was still segregation in place in many areas, for instance,” says Bynum. “There even existed a small credit union in the Black community I lived in which was run out of a man’s garage! That’s how people helped each other, by pooling their resources and working together. It was an enormous influence on me in my formative years. People were not allowed access to or credit from their local banks so they had to be innovative and create such opportunities for themselves. I saw the power and importance of such solidarity. The very suit that I often wore to college was paid for by my grandmother going to that gentleman’s garage,” he recalls. That very same credit union still exists to this day, on a much larger, nation-wide scale by the name of Self-Help.

Bynum, far left, with a group standing in front of a home built through Home Again, an initiative to rebuild homes on the Gulf Coast after Hurricane Katrina.

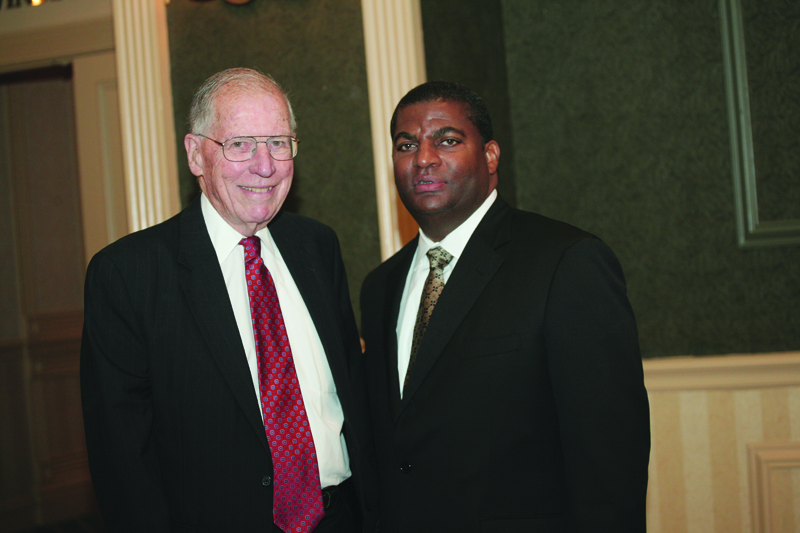

Bynum with former Governor William Winter.

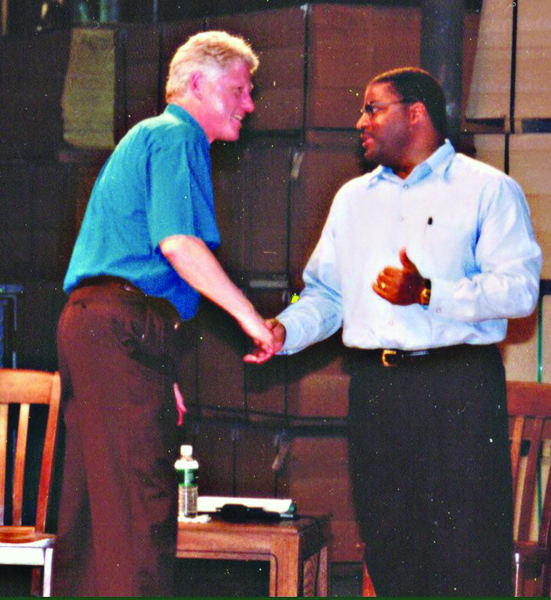

Bynum with former President Bill Clinton.

HOPE CEO Bill Bynum briefs the U.S. Treasury Department’s Community Development Advisory Board during an event commemorating the 25th anniversary of the Community Development Financial Institutions Fund.

HOPE CEO Bill Bynum speaks at the ground-breaking of Hope Credit Union’s Biloxi branch in 2005.

“I grew up always asking the question ‘Why’—and I certainly asked ‘why’ about many things I saw in those early years of my career: why couldn’t people band their resources together and help others? Why couldn’t communities become self-sufficient on their own? That type of insistent questioning led me to where I am today,” says Bynum.

Bynum did in fact get accepted into the University of North Carolina’s law school. But, his dream of becoming the next Thurgood Marshall had, by that time, been replaced by other dreams that his credit union work had prompted and created.

“In the mid-80s, I came to realize that economic opportunities could have more of a lasting impact on society’s well-being and so I made the decision to continue trying to increase and enlarge the scope of such opportunities for people who needed them,” says Bynum. “I previously had in my head that I was going to be the next Thurgood Marshall, but I thought that economic advancement might be more enduring and beneficial in the long run than even legal opinion.”

Bynum remained with Self-Help and witnessed the credit union grow exponentially and rapidly.

“We were able to branch out further to assist rural business owners and farmers, women-owned and people of color-owned businesses as well as helping many first-time homeowners” Soon, however, another change came for Bynum when he left Self Help in 1989 and went to work with the North Carolina Rural Center in Raleigh, which mainly provided assistance to micro-businesses in areas of that state that needed it.

“I ran a division for the Rural Center modeled after the Grameen Bank in Bangladesh.” says Bynum, “where, essentially, people pooled their resources together and made very small loans to others in their North Carolina community, a peer-supported network as it were. Modeled after this other bank we ended up becoming the largest micro-business program in the nation. Interestingly, the founder of the Grameen Bank visited us and we gave him a tour of North Carolina. This gentleman, Mohammed Yunus, later won the Nobel Peace Prize for the work he did in Bangladesh,” says Bynum.

At about the time he left Self Help, Bynum had married in 1988 to a lady he had met a few years earlier at a conference. Her name, ironically, was…Hope. Mrs. Bynum passed away a few years ago. The couple had a daughter, Blythe, in 1990.

“After studying at the University of Mississippi Medical Center, she is now the Chief OB-GYN resident at Virginia Commonwealth Hospital in Richmond, Virginia,” he says.

“God has plans for us and you really just never know,” says Bynum. “But, while in North Carolina I met a man named George Pennick who was the head of the Foundation For The Mid-South in Jackson and, until he recently retired, Headmaster at St. Andrews Academy. When I first met him, George was working in North Carolina at the Babcock Foundation, but was recruited by Governor William Winter, Billy Percy and others to come to Mississippi to start the Foundation. Funding was made available, and Bill Moyers even became involved with the process as an advisor—and the Mississippi Delta was targeted by the Foundation for the Mid-South. One of the components of the work was to have an economic development arm created and I was recruited to get that off the ground by George,” says Bynum. “I had never previously been to Mississippi, but it’s interesting: I had heard Governor Winter lecture in North Carolina about what was currently going on in the state, I was impressed. I had some preconceived notions about Mississippi—like a lot of people, you know—but Governor Winter dispelled those for me. I think that hearing and meeting him, ultimately, is what led to me to accept the job.”

Bynum made the move to the Magnolia State in 1994. “My wife and I decided to roll the dice, as it were, and give the job a chance for a couple of years,” says Bynum. His first impression of Jackson and Mississippi?

“Everybody I met was extremely friendly and my co-workers and the Board at Foundation For the Mid-South turned out to be some of the best people I’ve ever had the privilege to know and made friends for life. I liked Jackson and saw a lot of potential—and I’m still here,” Bynum chuckles. “So many wonderful people were helpful to me when I first came to Jackson: Harry Walker, Bud Robinson, Mike Espy and Robert Gibbs, who is on our Board now here at Hope—and that’s just to name a few.”

Bynum had been entrusted with a $1.5 million grant from the Pugh Foundation to “transform” the Mississippi Delta: that was his mission upon arrival in Jackson for his new job.

“It was a good start,” he says. “We launched the Enterprise Corporation of the Delta (ECD) and it didn’t take long to see that the needs of the businesses we were in place to help exceeded our funding. We had to seek out other resources. Around the same time I joined the Anderson Methodist Church in Jackson and the pastor revealed to me that he had been thinking of forming a credit union to act as an alternative to the payday lenders and check cashing businesses near the church. I got involved and that was the actual beginning of HOPE Credit Union. My day job was with ECD and I spent off time working with Hope as a viable alternative to the check cashers in the neighborhood.”

Around 2002, the ECD evolved and was absorbed into HOPE Credit Union. “We got other churches on board, across all denominational and racial lines, and opened an office in the Jackson Medical Mall,” Bynum says. “We began to grow rapidly and expanded into service and retail assistance—as well as housing—into the sectors where we could provide help and assistance. In 2004, we entered the New Orleans market to assist neighborhoods in and around the city. After Hurricane Katrina hit, HOPE found itself in the middle of the rebuilding process for residents in New Orleans and along the Mississippi Gulf Coast and were assisted greatly by Jim Barksdale in our efforts. We ended up providing financial counseling to over 10,000 families on the Coast as part of the State’s recovery effort along with helping hundreds of businesses in New Orleans. Over that time, we grew from about 4,000 members to over 9,000 and from a staff of 50 to 150,” says Bynum.

While Bynum and his staff were still catching their breath from the aftermath of Katrina, the financial meltdown of 2008-2009 hit—and it hard the rural areas Hope served hard.

“We were able to come in and provide assistance where traditional banks could, or would, not,” Bynum recalls. “In the Mississippi Delta alone, we took over banks in Drew, Shaw, Itta Bena and Moorhead, for example, and converted them to credit union branches. We also entered into the Memphis and Little Rock markets. Today we have a presence in Mississippi, Arkansas, Louisiana, Alabama and the Memphis, TN area. Our services have expanded and, frankly, we’re busier than ever,” says Bynum.

When asked to name the proudest moment of his career, Bynum answers, “In many ways, I think I would say it’s just a culmination of things. As beautiful as the Mississippi Delta is, it is also one of most economically-distressed areas of the country. People are stretched to their limits and beyond these days. To help these folks get on their feet, stabilize their lives and simply survive, is gratifying enough. Here we are in the midst of a pandemic and Hope is providing business loans to entrepreneurs in order to keep their doors open. My team has stepped up and done the impossible, really: they have helped those most vulnerable in our region and done so well, with timeliness and dignity. That’s what I am most proud of you. I’m glad we’re here to be able to help people.”

Perhaps too humble to name as career highlights and accomplishments Bynum also serves on the boards of the Aspen Institute, NAACP Legal Defense Fund, Prosperity Now, William Winter Institute for Racial Reconciliation and is a member of the US Partnership on Mobility from Poverty. Bynum also previously chaired the Treasury Department’s Community Development Advisory Board and the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau Consumer Advisory Board. A recipient of the University of North Carolina Distinguished Alumnus Award, Bynum’s honors include the John P. McNulty Prize (Aspen Global Leadership Network), Ned Gramlich Award for Responsible Finance (Opportunity Finance Network), National Entrepreneur of the Year (Ernst & Young/Kauffman Foundation), Rural Hero Award (National Rural Assembly), Pete Crear Lifetime Achievement Award (African American Credit Union Coalition) and Annie Vamper Helping Hands Award (National Federation of Community Development Credit Unions) .

Just this past June, Netflix announced a $10 million deposit in HOPE Credit Union as one of its first investments in a $100 million initiative to build economic opportunity in Black communities. In each southern state served by HOPE, for every dollar in net worth held by white households, Black households hold between ten and twenty cents.

Through Transformational Deposits, HOPE will import funds into these communities to make business, mortgage and consumer loans and provide other financial services that build wealth and foster economic mobility. Over the next two years, HOPE estimates the Netflix deposit will support financing to more than 2,500 entrepreneurs, home buyers and consumers of color.

“More people—and companies like Netflix—are seeing the importance of investing in communities and regions like the Mississippi Delta,” says Bynum. “When I was approached by the people at Netflix, I was immediately open to the idea and very appreciative—and impressed. We’ve been reached out to by other companies around the country since this announcement and I’m hoping we will have new, similar investments and partnerships soon,” says Bynum.

Bynum says it’s truly a blessing to be able to do work that he enjoys and that allows him to let his creativity and business acumen flourish.

“I’m committed to make a difference and I’m fortunate to work with a staff that shares that commitment,” he says. “I don’t have a whole lot of hobbies. But, I’m on a number of boards of organizations that share my commitment to helping others so…there you have it!”

Bynum, who resides in Jackson, loves to get out in the field and talk to the members and customers of HOPE Credit Union. “We rely on them to get it ‘right’ and we are accountable to them since they’re members,” he says. “I listen to their opinions and it helps me so much in my job and in what I do.”

A devoted and dedicated man of the community for many years over a fascinating career, Bill Bynum will no doubt continue to act as an advocate and leader for the South for many years to come.

We can only “hope.”