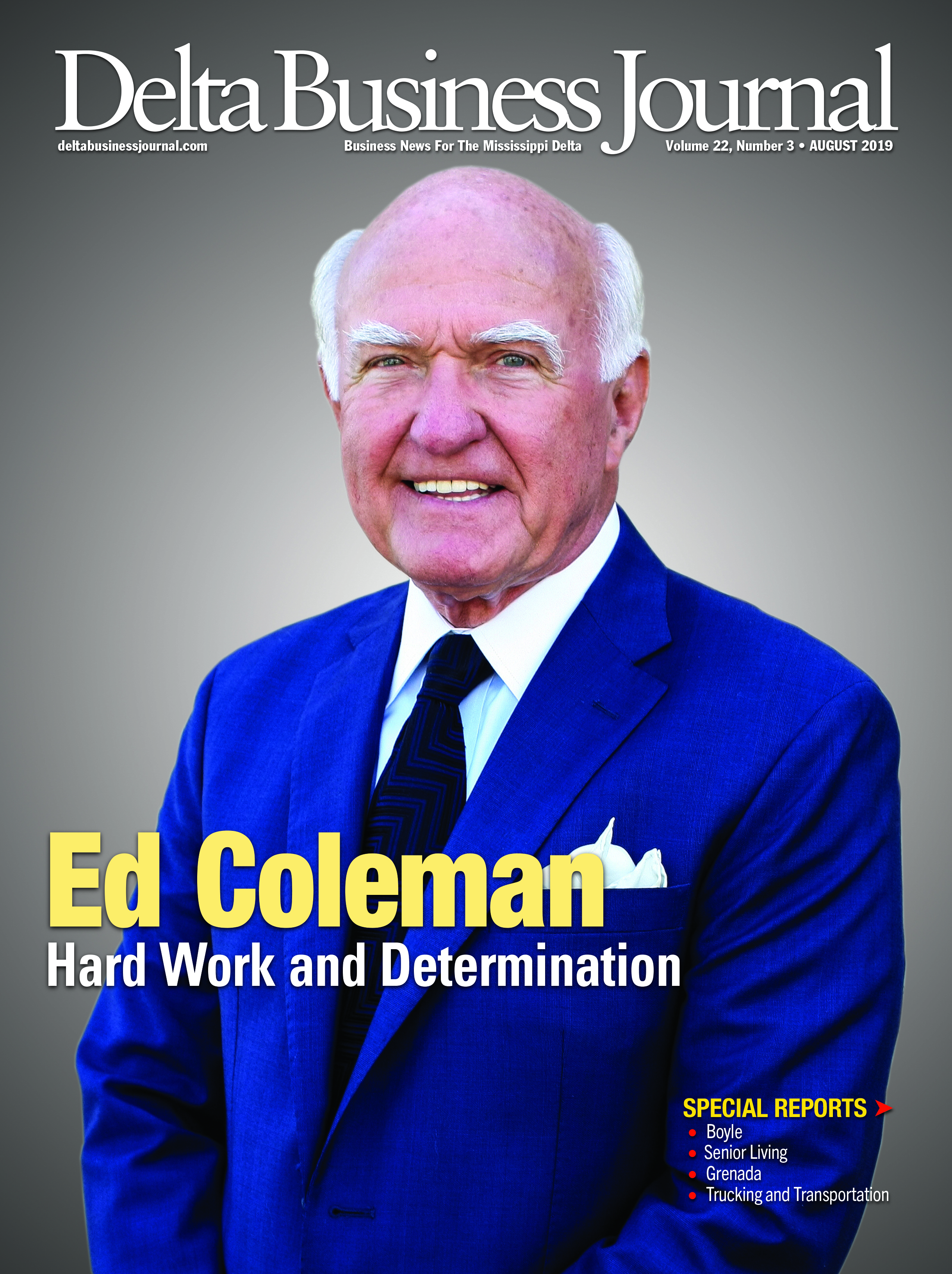

By Scott Coopwood • Photography by Holly Tharp

“I was born and lived the first part of my life on a dirt road,” says Ed Coleman of Cleveland. “Then, my family made a step up in life when we moved to a house on a gravel road. And when we moved to town into a white duplex, I thought we had arrived!”

Those early memories of that meager life in Charleston, Mississippi have stayed with Coleman to this day, and in many ways, they helped set the foundation for the course of his very successful business career. That fifty-eight-year career has taken Coleman from working at a small Layne water well drilling district in Cleveland to him helping build and run the largest water exploration and development concerns in the U.S. And then, toward the latter part of his career, that journey returned him to Cleveland where it all began to the exact location and building where he worked when he was twenty-one years old and a student at Delta State.

“It’s been a fascinating career,” says Coleman. “And I wouldn’t trade it for anything.”

Today, he is the owner of Mid South Water (midsouthwater.com) based in Cleveland, a company that specializes in Municipal, Industrial and Agricultural ground water development. The territory of Mid South Water, LLC not only covers Mississippi, but also stretches to parts of Tennessee, Arkansas and Louisiana. The company offers a wide range of services from initial groundwater surveys, to explorations, site selections, well drillings, pump designs and installations, the construction of water systems, geophysical logging surveys, well inspections, preventative maintenance services, and chemical treatment of water wells. The list of services doesn’t stop here. The bottom line: if it has anything to do with underground water, Coleman’s company fits the bill.

Today, he is the owner of Mid South Water (midsouthwater.com) based in Cleveland, a company that specializes in Municipal, Industrial and Agricultural ground water development. The territory of Mid South Water, LLC not only covers Mississippi, but also stretches to parts of Tennessee, Arkansas and Louisiana. The company offers a wide range of services from initial groundwater surveys, to explorations, site selections, well drillings, pump designs and installations, the construction of water systems, geophysical logging surveys, well inspections, preventative maintenance services, and chemical treatment of water wells. The list of services doesn’t stop here. The bottom line: if it has anything to do with underground water, Coleman’s company fits the bill.

Coleman spent most of his fifty-eight year career helping build the well-known Layne Christensen Company which is a global water management, construction and drilling concern. Many in Layne Christensen corporation have always given credit to Coleman as having played a significant role in building the company.

“With the exception of our founder, Mahlon Layne, no person has been as important to Layne’s longevity and success as Ed Coleman,” said Andrew B. Schmitt, the former CEO and President of Layne, upon Coleman’s retirement from Layne in 2003.

Hard work, determination, a common sense approach to things and equal respect for those working in the executive suite, district offices or in the field, have taken Coleman a long way from the small town of Charleston and those meager beginnings.

“We were very poor,” Coleman says reflecting on his life.

He says they still lived a good life with his mother the epicenter and driving force.

“My mother was a proud woman and she believed in working,” says Coleman. “And one thing she was always adamant about was being on time. In fact, she insisted that I be on time and to this very day I am. She was also big on cleanliness.”

Back in the 1940s, like so many other small Southern towns, Charleston, Mississippi, was very active for its size and it was almost free from crime.

“Everyone knew everyone,” he says. “We had our little groups like small towns used to have and even though it was tough and hard, we were happy.

“I remember when the war ended,” says Coleman of World War II. “I lost a first cousin in the war and he was the only son with four sisters. I was a little boy, but I remember gathering at his parent’s home which was a very sad day.”

In the fifth grade, Coleman entered the workplace delivering newspapers for the Commercial Appeal every morning. He later landed a job at a Chinese grocery store on Saturdays working from 7:00 a.m. to 11:00 p.m. The pay was $5.00 a day.

“There were no concerns about child labor laws back then, I was just glad to get it,” laughs Coleman. “But I learned many things about making money as a child.”

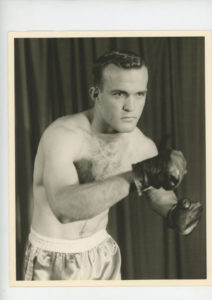

He later advanced to a better newspaper route working for the Memphis Press-Scimitar. But, in the seventh grade, Coleman found something that would literally change his life: the school boxing team.

He later advanced to a better newspaper route working for the Memphis Press-Scimitar. But, in the seventh grade, Coleman found something that would literally change his life: the school boxing team.

“Immediately, I was attracted to boxing,” he says.

However, because boxing competed with football, the Board of Education stopped the boxing programs in schools across Mississippi; but, that did not stop Coleman’s interest in the sport.

“Boxing is like other individual sports in that it’s all left up to you. No team mates to blame. Work extra hard and long and be successful,” says Coleman.

And like the other young teenagers in Charleston, Coleman also participated in numerous sports. But that also would come to an end.

One day at recess while he was playing baseball, he got trampled as he tried to block the third base. The collision broke his upper arm just below his shoulder.

“I had to wear a cast around my chest with my arm bent at the elbow and blocked up evenly with my shoulder,” he says. “Because of that, my friend, Ted Smith suggested I should learn how to play the trombone and baritone since my arm was positioned perfectly in the cast to play those instruments. I can’t say I really had much music ability, but I learned to read music very quickly.”

The second year of playing those instruments, Coleman was tapped to become a member of the Lion’s Allstate Band. The band made a trip to New York City where they participated in a parade with Mary Ann Mobley who was a majorette from Rankin County. According to Coleman, Mobley was just as nice then as when she later became Miss America and a Hollywood actress. It was the first time he had been that far away from Mississippi.

“I walked around with my mouth open while I was there,” laughs Coleman. “That trip was a great experience for a poor boy from Tallahatchie County.”

While in New York, Coleman bumped into a pleasant surprise.

“Four or five of us walked into a restaurant where I saw a black man working at the back of the restaurant,” he says. “I shouted, ‘hey Hambone’ and he ran to me and I to him and immediately hugged. I looked around and everyone in the place was looking at us, they didn’t know what to think and the group I was with wanted to run. Hambone had worked at the drug store back in Charleston before moving to New York and he was loved by everyone. Growing up, race really didn’t enter my mind in Charleston. I had black friends, played with other black children and just had a good time.”

Like his trip to New York, Coleman had another eye-opening experience when he was seventeen.

A friend who was a freshman in college was headed to Chicago for a summer job and asked Coleman if he would like to join him. The job was working for the railroad.

“That sounded good to me, but my mother absolutely refused to let me go,” says Coleman. “I begged her for days, then she finally caved, but told me she was certain I’d return home in a week or so because, since I was only seventeen, I wasn’t going to get a job.”

Coleman and his friend packed their bags and had another friend drive them ten miles to Oakland so they could hitchhike to Chicago from the side of Highway 51.

“Back then, you could do that,” laughs Coleman. “Today, you wouldn’t dream of it.”

Fifteen minutes after arriving on the side of the highway, a man picked them up and carried them all of the way to Decatur, Illinois.

“He dropped us off at a cafe and after we ate, we stepped outside and almost immediately caught another ride into Chicago,” says Coleman.

The next day, he applied for a job with the Elgin, Joliet and Eastern Railroad company. He and his friend walked into the Train Master’s office and filled out a job application. But, instead of writing down the actual year Coleman was born (1938), he put down the year before (1937) which made him appear to be eighteen years old so he could be hired. The man did not ask for any form of identification.

“I crossed my fingers when I filled out that application and hoped they wouldn’t somehow figure out the actual year I was born,” says Coleman.

He got the job and reported to work in the Southside of Chicago at the U.S. Steel Mill where the Elgin, Joliet and Eastern Railroad was headquartered.

Coleman became a fireman on a diesel engine.

“In the old days, a ‘fireman’ was the man who shoveled coal to the burner, but with a diesel engine, of course you don’t have to do that,” says Coleman. “I cleaned the cab, the windows and I’d sit on the left side of the engine watching the flagman outside give signals and I’d relay those to the engineer.”

One day, the engineer mentioned to Coleman his mother might rent him an extra bedroom in their home. Before that, Coleman was staying in a boarding house.

“They took me in like a family member and I lived with them off of Lakeshore Drive which back then was a very nice area,” says Coleman. “They had a boat and we’d go down to the Lake Michigan beach, ski and at least flirt with the girls. Living in Chicago that summer was a wonderful experience and I learned a lot about life there.”

Coleman returned to Charleston with $1,500 he saved from that summer job.

“Let me tell you, $1,500 was a lot of money back in those days,” he says.

One of the main things he learned that summer in Chicago, humbled him. Around 11:00 p.m. one night after getting off a work shift, Coleman walked to a bus stop and quickly discovered he did not have his wallet and no change in his pocket for the .25 cent bus ride. Even in 1955, the Southside of Chicago was a dangerous place at night.

“I was tired and probably looked pretty bad,” he says. “I didn’t know what to do, I had no money.”

It would have been a four-mile walk through that part of the city. Coleman had only one alternative and that was to ask someone for a quarter so he could ride the bus.

“Asking a stranger for money was the last thing I wanted to do,” he says. “But, the longer I thought about it, the more I realized I didn’t have any alternative. So, I walked up to one of the men standing in line and asked him for a quarter. The man reached in his pocket, gave me a quarter, and he never looked at me, making me feel even worse. I’ve never forgotten that feeling.”

That taught Coleman how to be humble and from that day on he knew if ever called upon to help someone in need, regardless if that need was small or large, he was going to help them.

After graduating from high school, Coleman pursued his dream of boxing and attended Northwest Junior College in Senatobia, Mississippi where several boys trained and boxed in various Arkansas tournaments. He joined the group. At one tournament in Osceola, Arkansas, his life would change course again after meeting Hubert Boykin who was in Osceola to watch the tournament. Boykin encouraged Coleman to enroll at Delta State and box for him. Boykin was the long time Chancery Clerk in Cleveland and had personally organized the Cleveland Athletic Club strictly for boxing. Coleman agreed to do that and for a year or so he and others from Cleveland boxed for Boykin.

“I loved Delta State and being in Cleveland,” says Coleman. “Mr. Boykin would drive Henry Mosco, Sr. and me on several occasions to Grenada and put us on the train headed to New Orleans. We’d stay down there for a few days, box and come home. Mr. Boykin did so much for so many young people. He certainly helped me and made a difference in my life. He was a good man.”

In New Orleans, Coleman and Mosco worked out and trained in the same gym with Ralph Dupas, who was the world welter weight champion at the time and Willie Pastrano, the world light heavyweight champion.

“I had the opportunity to work out with Dupas several times and that experience proved to me that my aspiration of being a professional fighter wasn’t going to happen.”

Coleman continued boxing as an amateur and in 1960, he received the Outstanding Open Fighter in Mississippi award.

Back at Delta State though, Coleman’s plans were changing. He decided to exit boxing and realized to graduate from Delta State, it was going to take him five years instead of four.

“When I told my mother that like most of my friends, it was going to take me five years to finish college, I remember her exact reply. She said she had agreed to pay for a four-year education and that she would pay for years one, two, three and five, but that I’d have pay for year four,” laughs Coleman. “I told her I didn’t have the money to pay for a year of college and she responded that perhaps I had better find a job!”

“When I told my mother that like most of my friends, it was going to take me five years to finish college, I remember her exact reply. She said she had agreed to pay for a four-year education and that she would pay for years one, two, three and five, but that I’d have pay for year four,” laughs Coleman. “I told her I didn’t have the money to pay for a year of college and she responded that perhaps I had better find a job!”

Coleman met with Boykin and told him about his predicament. Boykin knew about a position with Layne Central Company in Cleveland that might be available and told Coleman he would make a call. The phone call Boykin made would ultimately place Coleman on a fifty-eight year career in the water business.

“I interviewed with Mr. Ted Arbogast at Layne and he hired me,” says Coleman. Arbogast saw something in Coleman.

“I went to work for a very fine old gentleman who had learned the business from the ground up,” he says. “I tried to prove to him he couldn’t run me off and he tried his best to see how close he could get to it.”

On his first day of work, Coleman arrived dressed nicely and Arbogast handed him a five-gallon bucket of silver paint and told him to go outside and paint 800 feet of steel screen.

“I can remember thinking ‘what have I gotten into here?’” says Coleman. “At the end of the day, I was covered in silver paint from top to bottom. For the rest of that week I painted that screen and never opened my mouth. At 5:00 p.m. that Friday, Mr. Arbogast said, ‘Well, I guess you have painted enough so we’ll do something else tomorrow.’ And he was talking about Saturday! So, I returned the next morning and started working in the shop. Then, on Monday he put me on a rig in the field. No one at Layne cut me any slack and eventually I learned everything I could learn about the operation. I look back now and realize Mr. Arbogast treated me like his own son.”

As a result, from those early beginnings and because of Coleman’s stickability, he eventually worked in every department at Layne. Those experiences would prove invaluable as Coleman rose through the ranks starting out in 1961 at Layne as a sales trainee, then becoming a sales representative in 1963. At the age of twenty-eight, he was promoted to District Manager which was a huge move. Then, he became a Regional Manager in 1974 and two years later in 1976, Coleman became a Regional Vice President.

As the corporation grew, in 1979, Layne promoted Coleman to Senior Vice President and he had to move to the corporate offices in Kansas City.

“In Kansas City, first, I worked to develop a training program and I was also involved in recruiting, and really just about everything else,” he says. “I developed the first training program in the Layne 2,300 employee organization based on what I had learned back in Cleveland.”

In June of 1985 Coleman was promoted to Executive Vice President of Layne Christensen. He credits his old mentor, Arbogast for laying that early foundation to training and the basics.

“I went from a private to publicly traded company, then to a big $2 billion conglomerate, then back to being owned privately, then to a publicly traded company,” laughs Coleman. “I enjoyed it all.”

During his career with Layne, Coleman assisted regional and district managers with budgets, provided support in negotiations, business development and project completion as well as troubleshooting problems. He also took on many special assignments that came directly from the Layne President and CEO with several of those assignments overseeing acquisitions of other product lines, entire companies, asset management, and reviews of negotiations and collective bargaining agreements with several unions. Coleman was also responsible for the profitable operation of the district offices as measured in terms of financial return and the preservation of capital funds invested in the company. And, Coleman’s responsibilities did not end there. In fact, they seem to almost be endless. Numerous business development trips were made to Peru, Guatemala, Mexico, the Bahamas and Jamaica.

During his career with Layne, Coleman assisted regional and district managers with budgets, provided support in negotiations, business development and project completion as well as troubleshooting problems. He also took on many special assignments that came directly from the Layne President and CEO with several of those assignments overseeing acquisitions of other product lines, entire companies, asset management, and reviews of negotiations and collective bargaining agreements with several unions. Coleman was also responsible for the profitable operation of the district offices as measured in terms of financial return and the preservation of capital funds invested in the company. And, Coleman’s responsibilities did not end there. In fact, they seem to almost be endless. Numerous business development trips were made to Peru, Guatemala, Mexico, the Bahamas and Jamaica.

But all good things come to an end and after forty-three years and just before going into one more large acquisition, at sixty-three Coleman decided it was time to retire. The ride had been great and long.

“I retired and almost immediately was miserable,” he says.

After some negotiation, Coleman moved back to Cleveland in 2003 and bought the Cleveland property and certain other assets, changing the name to Mid South Water. For the next ten years, he grew Mid South Water and in 2014 decided to sell the company and finally retire. But, like the first “retirement”, the second one did not last long either.

Coleman sold the company to Alsay Water Holdings in Houston, Texas. He continued as President for two years overseeing the Cleveland operation, but on a reduced work schedule. It was not long before Coleman grew concerned and had questions about Alsay’s management style. He also questioned the financial condition of Alsay. And while the Cleveland location continued to produce in a profitable mode under Coleman’s direction, Alsay stumbled in other jobs. Two years after selling Mid South Water, and concerned about the direction the company was heading, Coleman bought back Mid South Water.

“That repurchase took place on June 1, 2017,” says Coleman. “The company continues to be recognized as a leading water well contractor in the Mid-South.”

“That repurchase took place on June 1, 2017,” says Coleman. “The company continues to be recognized as a leading water well contractor in the Mid-South.”

And retirement for a third time?

“When you have been in the business as long as I have, it becomes a passion,” says Coleman who will have been in the water business for fifty-nine years next March, 2020.

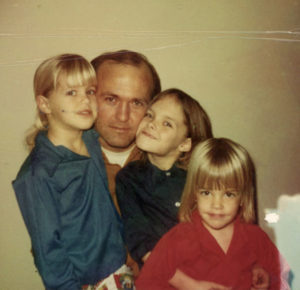

In 1993, Coleman’s wonderful wife of thirty-one years, Gai and mother of their three daughters died of cancer.

“She had been my major supporter and encouraged me in every possible way,” Coleman says.

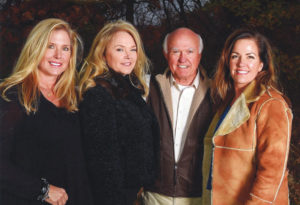

In 2005, Coleman married Kay Youngblood who is from Monroe, Louisiana. Today, Kay’s office is across the hall from Ed’s and she plays an important role as office manager and Vice President of Finance at Mid South Water.

from Ed’s and she plays an important role as office manager and Vice President of Finance at Mid South Water.

“I’ve been blessed far more than most,” says Coleman. “I love Cleveland and the Delta and while I could move back to Kansas City tomorrow, there is no place I’d rather be than right here in Cleveland and the Mississippi Delta.”