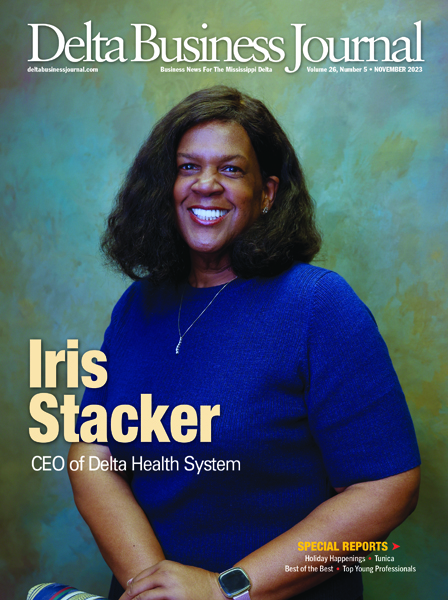

Chief Executive Officer of Delta Health System

By Becky Gillette • Photography by Johnny Jennings

Delta Health System Chief Executive Officer Iris Yeldell Stacker started working at her father’s medical practice when she was only about fifteen. At age sixteen, her father told her she needed “a real job” working at the hospital, which was then known as the Delta Regional Medical Center (DRMC). She got a job as a tray girl in the cafeteria.

“The second year the cafeteria was being refurbished and we had to cook at a local school and bring the meals to the hospital,” says Stacker. “I was doing that with friends, and we got the van dirty. It attracted flies. They made us clean out maggots. I was once cleaning out maggots and now I am the CEO.”

Stacker has more than forty years of experience in healthcare and was vice president and system compliance officer at Delta Health System prior to being made interim CEO in July 2022 when the former CEO resigned.

“At the time, we knew we were having some financial difficulty but didn’t know how bad it was,” says Stacker. “We had tremendous expenses relating to higher costs for Covid and a great deal of uncompensated care. We had added two additional hospitals to our system, the Highland Hills Medical Center in Senatobia and Northwest Regional in Clarksdale. The concept for the Mississippi Delta was that we felt if we could band facilities together, we would be in a stronger, better contracting position and be able to reduce costs.”

What they did not foresee was the effects and after effects of Covid. On top of that, Delta Health System—like most hospitals–was having issues with inadequate managed care reimbursements. Another factor was that Mississippi had not accepted the Medicaid expansion to help provide healthcare coverage for low-income people.

“Then we were also faced with having to pay back advanced payments that Medicare had given us for Covid and, at that time, we didn’t have the money readily available,” says Stacker. “We ended fiscal 2022 with a $29 million loss.”

They went into an “all systems go” response, banding their team together and looking at ways to decrease costs and increase revenues. They renegotiated contracts and agreements, took an inventory of service lines that were profitable and non-profitable, and then took advantage of FEMA Covid grants.

“A total of $9-million in FEMA grants kept us alive for a number of months,” says Stacker. “We had a lot of people praying. I’m a firm believer in the power of prayer. We had to divest the other hospitals. We sold Highland Hills to Tate County and the other hospital was assumed by Coahoma County, although we still owe them payments until 2025. We are now managing only one acute care hospital in Washington County. In doing this, we are foreseeing that by the end of fiscal 2023, we will show a small profit. It won’t be much, but at least it won’t be a loss.”

Another thing that hurt all three hospitals was losing a lot of nurses during Covid. Nurses quit and hiring contract travel nurses was very expensive with costs ranging from $125 to $175 per hour.

“During Covid we lost at least 2,000 nurses in Mississippi who did not renew their licenses,” says Stacker. “We still have not really recouped as far as our nursing staff. We are still using some contract nurses. There are larger hospitals in bigger cities still paying high salaries.”

During Covid, prices for everything soared. “When my costs go up at the hospital, I don’t have anyone to pass them on to,” says Stacker. “The Medical Center has to absorb the increased cost due to reimbursement issues.”

Another problem is insurance companies and government programs failing to pay—sometimes even after preauthorization.

“There needs to be some reform with our managed care companies for Medicare and Medicaid,” says Stacker. “It doesn’t have to be a Medicaid expansion, but we need some assistance for the working uninsured so they could have coverage. Our governor said he is looking into some of the authorization issues. We need more control over our insurance companies and our healthcare costs. We need to come up with a model so all our communities can have some type of healthcare available so people don’t have to travel too far.”

Stacker says if rural hospitals close and people have to drive an hour or more for care, that is a major problem for people without transportation. Many patients have more than one serious health problem such as diabetes, renal failure and congestive heart failure.

“Our renal disease is off the charts,” says Stacker. “Then, we had the news the other day that Mississippi is the most dangerous state in the country to have a baby. We are working on grants to address our maternal care and infant mortality.”

Stacker was born in Nashville. Her father, Dr. James Burl Yeldell graduated from medical school on June 12 and her mother, Gloria Sisson Yeldell, gave birth to Iris June 13, joining her two brothers and sister. The family then moved to Greenville.

Medicine has changed dramatically since the days when her maternal grandfather, Dr. Sarne Nathaniel Sisson, would go out in the middle of the night to deliver babies and come back with baskets of fruits and vegetables. Today, many rural hospitals don’t even have labor and delivery services.

Stacker started her medical career at Humphreys County Memorial Hospital in Belzoni after graduating from Greenville High School in 1977 and attending Ole Miss in Oxford for two years before finishing up a degree in health information management at the University Medical Center at the School for Allied Health Professionals in Jackson. She was Director of Medical Records at Humphreys County Memorial before moving to take the same position at Jefferson County Hospital in Fayette. A couple years later, she came back to Greenville and started working at The King’s Daughters Hospital.

“That was the dream job of my life,” she says. “I started as Assistant Director, then became Director of Medical Records, was promoted to become Director of Case Management and Regulatory Compliance, and then added Directorship of Case Management. At the end of my career at The King’s Daughters Hospital, I was the Quality Director.”

She recalls it was April Fool’s Day of 2005 when she moved to the Delta Regional Medical Center after the Washington County Supervisors purchased The King’s Daughters Hospital. Stacker’s first position when she began working at Delta Regional Medical Center was Compliance Officer and Director of Health Information Management. In 2018, She was promoted to be a member of the Delta Health System Senior Leadership Team as Vice-President of Compliance & Support Services.

One of the beauties of sitting in her seat is that she has worked from the ground up, so she understands the intricate details as far as coding, billing and denial management. She knows the struggles her employees face and how hard it is to overcome some of the barriers.

Going forward, Stacker’s goals include adding more family practice and specialists to an area that is a physician desert. Delta Health System started the first family practice residency in the Delta with the first class of six graduating in June. Four stayed in the Delta and one went to Jackson. They are working hard to be more competitive in order to attract more specialists.

“We need another cardiologist, an OB-GYN and an ear, nose and throat specialist,” says Stacker. “We are looking at ways to increase revenues and bring more physicians to the community.”

Delta Health System also now has a mobile unit equipped with x-ray equipment, an EKG monitor and other medical equipment to be used in underserved areas. The system has also partnered with the YMCA where people can use the facility free for six weeks. Seminars are held on issues such as controlling blood pressure, reducing cholesterol, glucose monitoring and weight control.

“I am proud to work with the hospital team that feels strongly about working within the community promoting wellness to people of all ages,” she says. “This includes health fairs, school pipelines, business partnerships and working with our city and county. Also, it is vital for us to work directly with students mentoring them to work in the healthcare profession in all positions and fields.”

Stacker frequently goes to civic club and community stakeholder meetings so people know what is going on in the hospital and the many services available including outpatient clinics.

“Hospitals are vital to the growth of your community,” she says. “Industries aren’t going to want to come to your area if you don’t have a hospital.”

Delta Health System has a huge economic impact with 869 employees and forty-seven physicians. There are about 142,000 people in their six-county service area.

Stacker is active with a number of civic clubs including Kiwanis and the Rotary Club.

Two recent acknowledgements of her leadership and community service were being named one of the Women in Rotary honored in 2023 and Hot Tamale Festival Queen—an event that draws about 10,000 people.

She goes to the gym to stay healthy and manage stress and enjoys traveling with former high school classmates and spending time with her four children.

“I enjoy and rely on my church life and some of the best friends in the world to bring me joy and keep me grounded,” says Stacker. “My boyfriend lives in Houston, Texas, so traveling is a big part of my life which I find to be extremely fulfilling. In fact, I often wonder how I manage to fit in all my activities.”

She follows the example of her parents and grandparents who believed in public service.

“God put us on Earth to help each other,” says Stacker. “Some days, my job can be overwhelming. It is hard. It takes a lot out of you. My community educated me, groomed me and made me the woman I am today, so why wouldn’t I give back everything I can? Our town is going in great directions, and I am just proud to be part of it. I truly am.”