By SCOTT COOPWOOD, Publisher, Delta Business Journal

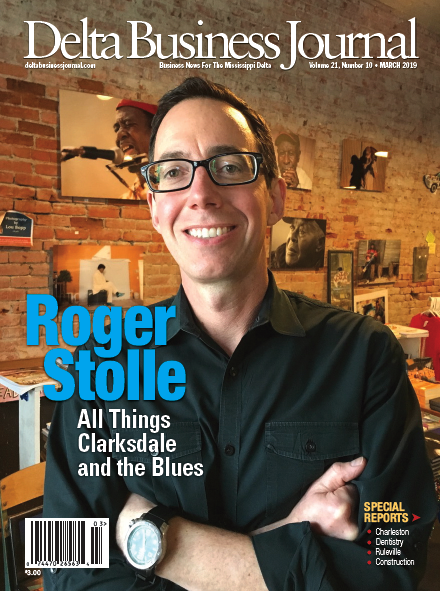

Roger Stolle’s hometown of Dayton, Ohio, is just over 650 miles from Clarksdale, Mississippi; however, growing up in Dayton, he didn’t realize his heart was already deeply rooted in the soil of the Mississippi Delta. In 2002, he moved to Clarksdale, and his vision and efforts over the past seventeen years have had a significant impact on the town. During this time he has established one of the most unique blues and folk art stores on the globe (Cat Head); contributed to a worldwide blues radio show originating from Clarksdale on SiriusXM Satellite Radio; helped create the leading blues festival in the state (The Juke Joint Festival); spearheaded the movement of offering live music in Clarksdale seven nights a week all year long; authored books on the blues; produced documentaries and blues records by some of the Delta’s most noted practitioners; and he has taken these blues musicians across the world where they have performed at many of the most well-known blues festivals. And along the way, Stolle has appeared in national magazines, newspapers, and on TV promoting Clarksdale and all things blues.

Roger Stolle’s hometown of Dayton, Ohio, is just over 650 miles from Clarksdale, Mississippi; however, growing up in Dayton, he didn’t realize his heart was already deeply rooted in the soil of the Mississippi Delta. In 2002, he moved to Clarksdale, and his vision and efforts over the past seventeen years have had a significant impact on the town. During this time he has established one of the most unique blues and folk art stores on the globe (Cat Head); contributed to a worldwide blues radio show originating from Clarksdale on SiriusXM Satellite Radio; helped create the leading blues festival in the state (The Juke Joint Festival); spearheaded the movement of offering live music in Clarksdale seven nights a week all year long; authored books on the blues; produced documentaries and blues records by some of the Delta’s most noted practitioners; and he has taken these blues musicians across the world where they have performed at many of the most well-known blues festivals. And along the way, Stolle has appeared in national magazines, newspapers, and on TV promoting Clarksdale and all things blues.

His journey to this Mississippi Delta began on August 17, 1977.

“That’s the day after Elvis died,” he says. “The radio, TV, and mall PA was playing Elvis’s music and some of it really stuck with me.”

Stolle was ten years old, and before that moment, music had never entered his mind. From that moment on, he began listening to Elvis and the various Sun Records recording artists. His musical interests later expanded into rhythm and blues and rock music. But things changed when he stumbled scross the blues. That started a fire that still burns in him to this very day.

listening to Elvis and the various Sun Records recording artists. His musical interests later expanded into rhythm and blues and rock music. But things changed when he stumbled scross the blues. That started a fire that still burns in him to this very day.

“I had a cheap cassette recorder, so I would tape music off the radio and TV, and when we made our weekly Sears run, I’d hit their record department and buy 45s with the songs I liked,” he says. “I learned a British guy named, Eric Clapton was basing his music on the blues. So, I’d go down to the local bookstore and look through the music magazines for interviews with Clapton.”

Stolle made notes of the musicians Clapton mentioned, and then he looked for those artists. Specifically, Muddy Waters, Buddy Guy, Albert King, and Robert Johnson. Along the way, he realized rock acts like Led Zeppelin and The Rolling Stones were also covering old blues songs, and that led to more research.

Stolle made notes of the musicians Clapton mentioned, and then he looked for those artists. Specifically, Muddy Waters, Buddy Guy, Albert King, and Robert Johnson. Along the way, he realized rock acts like Led Zeppelin and The Rolling Stones were also covering old blues songs, and that led to more research.

Music became an obsession during his teens. Then, when he enrolled at the University of Cincinnati, things kicked into high-gear. That is when Stolle finally had the opportunity to see live blues at a club called Bogart’s as well as a club back in Dayton called Gilly’s. He saw performances by Buddy Guy, Bobby “Blue” Bland, Little Milton, R.L. Burnside, and others.

“It’s funny, I saw Burnside at Gilly’s in 1988, and the next time I saw him was at Junior Kimbrough’s juke joint in Chulahoma, Mississippi, in 1996,” says Stolle. “Talk about two different cultural experiences!”

After graduating from UC in 1989, Stolle landed a job as a copywriter in the advertising department of Elder-Beerman—a regional department store chain that produced their marketing needs in-house. Stolle worked in every area of the department. That experience was invaluable to his career.

“I eventually landed a senior position at Elder-Beerman, and at the end of 1994, I was recruited for a management position in St. Louis, Missouri,” says Stolle. “I started February 5, 1995, as copy manager for Venture Stores in-house group.”

By mid-1998, he was managing the entire department at Elder-Beerman that consisted of writers and graphic designers. In July 1998, he joined May Company where he managed a department of fourteen graphic artists, production artists, production coordinators, and he oversaw other marketing positions. May Company provided branding for May’s department store chains, including Famous-Barr and Lord & Taylor. Because most of the items were manufactured in Hong Kong, Taiwan, or Eastern Europe, Stolle regularly travelled overseas for meetings, inspections, and packaging approvals.

July 1998, he joined May Company where he managed a department of fourteen graphic artists, production artists, production coordinators, and he oversaw other marketing positions. May Company provided branding for May’s department store chains, including Famous-Barr and Lord & Taylor. Because most of the items were manufactured in Hong Kong, Taiwan, or Eastern Europe, Stolle regularly travelled overseas for meetings, inspections, and packaging approvals.

And while he continued honing his marketing skills for his job, on the side he also continued studying the blues and regularly flying from St. Louis to Chicago to attend performances by most of the country’s iconic blues artists. Yet, until he moved to St. Louis in 1995, it had not occurred to him to skip the fountain and go straight to the well. It took moving to within five hours of Clarksdale for that to happen.

Stolle’s refers to his first trip to the Mississippi Delta as “the dead man blues tour.” He thought the music and the people behind it had died long ago. On that first trip, he had planned to visit grave sites and walk where his musical heroes had once walked.

“It turned out there were still jukes and blues folks, but the music’s local popularity was in decline,” he says. “There was a living, breathing blues culture, and on that first trip I also stumbled across something I had heard of, but never experienced—Southern hospitality. I’d drive back to my advertising job in St. Louis on a Sunday afternoon and look over my shoulder at the border and see the state signs that at the time read, Mississippi: Feels Like Coming Home. And, that’s exactly what it felt like. I’d cross the border and immediately start thinking about the next time I could return.”

“It turned out there were still jukes and blues folks, but the music’s local popularity was in decline,” he says. “There was a living, breathing blues culture, and on that first trip I also stumbled across something I had heard of, but never experienced—Southern hospitality. I’d drive back to my advertising job in St. Louis on a Sunday afternoon and look over my shoulder at the border and see the state signs that at the time read, Mississippi: Feels Like Coming Home. And, that’s exactly what it felt like. I’d cross the border and immediately start thinking about the next time I could return.”

But, moving to Clarksdale would mean leaving a secure job on the executive level at one of the most prominent businesses in St. Louis.

“When I finally decided to resign and move, my boss refused to believe that it wasn’t just a ploy to get more money,” laughs Stolle. “He started opening up the drawers in his desk looking for a pen and a piece of paper. He said, ‘Ok, what square footage will your store have?’ because he wanted to show how a retail blues store in Mississippi would not make the money I was making at May Company. He just couldn’t understand I was moving for a mission and not just a paycheck.”

Stolle. “He started opening up the drawers in his desk looking for a pen and a piece of paper. He said, ‘Ok, what square footage will your store have?’ because he wanted to show how a retail blues store in Mississippi would not make the money I was making at May Company. He just couldn’t understand I was moving for a mission and not just a paycheck.”

Stolle spent a year preparing for the move, and in May 2002 with a business plan firmly in place, he move and became a full-time resident. By July of that year, Stolle had opened Cat Head. From his previous trips, he knew several of the town’s leaders such as Bubba O’Keefe, Bill Luckett (co-founder with Morgan Freeman of Ground Zero Blues Club), Sarah Moore (Sarah’s Kitchen), John Ruskey (Quapaw Canoe Co.), Maie Smith (Delta Blues Museum), Panny Mayfield (Sunflower River Blues Festival), and Terry “Big T” Williams (blues guitarist).

“Back in the summer of 2002, Clarksdale’s blues scene was sporadic,” says Stolle. “Ground Zero Blues Club was up and running mostly featuring blues on the weekends, but sometimes an occasional rock band also performed. I actually convinced the old No Depression magazine to cover the scene here, and they reported to readers they’d heard a heavy metal band at Ground Zero. There was no reliable live blues Sunday, Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, or Thursday and nothing during the holidays. Even then you could still end up with the occasional Friday or Saturday night where there wasn’t any blues being played in town.”

Stolle knew that it was next to impossible to claim to be something, i.e. Crossroads of the Blues, without exactly being that.

“If we wanted to claim we were the ‘Crossroads,’ or say to the world ‘we’re ground zero for the blues,’ then we had to be those things, especially in order to try to rebuild downtown based on blues-based tourism,” says Stolle. “We just couldn’t say it; Clarksdale had to be the blues town.”

“If we wanted to claim we were the ‘Crossroads,’ or say to the world ‘we’re ground zero for the blues,’ then we had to be those things, especially in order to try to rebuild downtown based on blues-based tourism,” says Stolle. “We just couldn’t say it; Clarksdale had to be the blues town.”

All of the pieces were there — old buildings, blues musicians, Delta characters, blues history, and a trickle of what Stolle called the two-hour visitor.

“We just needed to pull the scene together and make it a reliable offering,” he says. “Then, and only then, could we really promote our town by all means necessary.”

Stolle will never forget attending a public meeting at city hall shortly after moving to town. At the city hall meeting, a man stood and said, “blues ain’t gonna save our town.” He also added, “and I’m tired of hearing about the blues.” Stolle wondered if the man’s comments represented how many felt.

“That really struck me,” he says. “The blues wasn’t going to save anything on its own; that was only something like a Nissan plant could do. However, blues could be the first piece of the puzzle. In fact, it was the only piece of the puzzle we had to play back then. The thing about puzzle pieces is that you add on to them until you have a complete picture.”

Stolle was convinced Clarksdale could become the blues town in Mississippi and perhaps the South. The first step was making sure live blues music was offered every night of the week, and at the same time several blues festivals needed to be created to bring in the larger tourism numbers and worldwide publicity. If this could be accomplished, it would lead to more money coming into community.

“As a former tourist myself, I knew someone doesn’t just come to hear a band and then go home,” says Stolle. “Overnight tourists book hotel rooms, eat in restaurants, enjoy the museum offerings, shop at the stores, and tour the entire region to see the other historical spots. Bottom line: they spend money!”

And, Stolle says tourists bring something else to the table that is equally important, “A cultural exchange occurs, locals exhibit Southern hospitality and visitors bring outside experiences to our collective knowledge base, which presents a win-win for everyone.”

But, organizing a solid blues scene had to be the first step to sell the “brand.”

In 2003, Stolle began booking music for Ground Zero Blues Club. He worked closely with Luckett to expand Ground Zero’s musical offerings to four nights a week—Wednesday through Saturday. At the same time, he also worked with Sarah Moore at Sarah’s Kitchen to better publicize her sporadic Thursday night music offerings. He then partnered with Red Paden to make his juke, Red’s, a more predictable blues venue that began to feature music every Friday and Saturday. After organizing Wednesday through Saturday with at least one blues show per night in Clarksdale, the next bridge to cross was offering live music during the remainder of the week.

“People thought Sunday, Monday and Tuesday nights were loser nights because locals were unlikely to come out and support music during those nights,” says Stolle. “Understandably, locals thought like locals. But we needed something that ran like clockwork.”

Fortunately, Art and Carol Crivaro moved to Clarksdale from Florida and opened Bluesberry Café and one of Stolle’s music-playing Cat Head employees, Sean “Bad” Apple from Pennsylvania, agreed to perform on Monday nights at the cafe. Their goal was to capture visitors who were passing through Clarksdale after a weekend in Memphis or New Orleans.

“It took a while for it to catch on, but for years now, Monday nights are jamming at the Bluesberry Cafe,” says Stolle.

A short time later, Stan Street moved to Clarksdale from Florida and opened Hambone. Street decided to offer music on Tuesday nights, and now that is one of the more exciting nights in Clarksdale.

“Later on, our second Australian couple moved here and opened Levon’s, which offers live music on Sunday afternoons,” says Stolle. “And Red Paden expanded to Sunday nights. We also have music out at Shack Up Inn and Hopson Commissary most weeks, some of which is blues.”

Today, Clarksdale offers live music every night of the year.

“Even I’m amazed, but it didn’t just happen,” Stolle says. “All of this is the result of a community coming together and coordinating the offerings. We now hold over a dozen festivals each year, so we really have become Bluestown, USA.”

While the nightly musical offerings have helped build Clarksdale’s brand and brought in visitors, the creation of the annual Juke Joint Festival has taken that brand worldwide. Today, it is one of the most well-known blues festivals in the world.

Leading up to the creation of the festival, Stolle says he and O’Keefe would sit for hours and brainstorm about what they could do to bring back the town through blues and cultural tourism.

“We shared ideas and had a working ‘to-do’ list,” says Stolle. “On January 28, 2004, Bubba walked through the front door of Cat Head and said, ‘That idea we’ve been talking about, let’s do it!’ I asked him which idea he was referring to, and he shouted, ‘that Juke Joint Festival’. So away we went.”

First National Bank in Clarksdale agreed to give O’Keefe a loan to help finance the festival and in April 2004 the first Juke Joint Festival was launched with only a handful of day stages and five venues at night that offered live music. Vendor tents the first year totaled fifteen in all. As a comparison, in 2018 the Juke Joint Festival offered thirteen stages of live music during the day and twenty-two venues at night that featured one hundred bands. Just under one hundred vendors also displayed their items last year. Now, over 7,500 people attend the festival each year and hotel rooms in Clarksdale are booked a up to two years in advance. And where are people coming from? During the 2016 festival, volunteers canvased the crowd, and their research revealed attendees had come from twenty-eight foreign countries, forty-six states and fifty-four counties in Mississippi.

Stolle says ‘Juke Joint’ has become a regular phrase in daily conversations about downtown revitalization and new festival events.

“Several of our modern downtown businesses point to it as a factor in their decision to open up in a tired, old downtown that most had given up on,” he says.

And while he and O’Keefe felt they could produce a respectable blues festival, they also wanted to create an event the local non-blues families would also attend. Toward that end, O’Keefe suggested the festival should include some “small-town fair” offerings.

“I remembered seeing racing pigs at a fair in Indiana one time,” says Stolle. “I tracked them down and booked them.”

Then, Stolle and O’Keefe heard about monkeys riding dogs herding sheep over in Pontotoc.

“One of our core organizers, Nan Hughes, found them,” says Stolle. “Our theory was that everyone wants to see a pig race or a monkey ride a dog and once people were standing together, Southern hospitality would take over. And it did. This gave our festival and our message of blues tourism and downtown revitalization some legs.”

The early business plan created by Stolle and a handful of others back in May 2002, has worked and Clarksdale is a far different town today than it was when Stolle first arrived. At least thirty-five overnight apartments are now located downtown as well as the new twenty-room Traveler’s Hotel. The Auberge Hostel, where Madidi restaurant was located, is soon to open, and many of the spaces that were empty back in 2002 are now filled with businesses. Other offerings include the popular Shack Up Inn just outside of town that has grown from six shacks to sleeping up to a hundred people several nights a week and Clarksdale’s three-year-old Hampton Inn is constantly fully booked. Renovations are underway to refurbish the old Rodeway Inn, and at least six or seven restaurants are now open in downtown Clarksdale that didn’t exist in 2002. The Delta Blues Museum has undergone expansions over the years, and it continues to anchor Clarksdale in many ways. Like Stolle, others who were once visitors have fallen in love with the town, and seeveral have moved there from California, Seattle, Portland, Oklahoma, Chicago, New York, New Orleans, Boston, Maine, Florida, Australia, England, and from other distant places. As designed, the music came first, and the infrastructure followed.

That comment at the mayor’s meeting, “Blues ain’t gonna save our town,” obviously fell on deaf ears.

“It definitely saved the downtown, and that’s the heartbeat,” says Stolle. “We still have work to do, but because of blues we’ve attracted the players who can help with the other non-music stuff. The jury may still be out, but our case is strong.”