By Becky Gillette

Photos Courtesy of Connect Americans Now

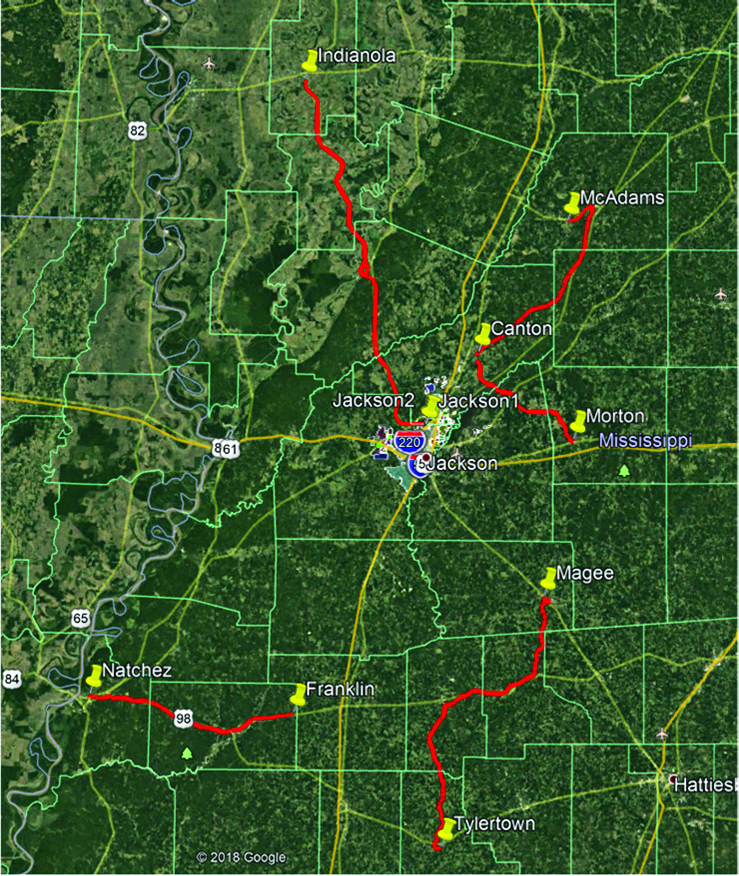

Two major efforts are underway to help “bridge the digital divide” by providing reliable broadband service to rural parts of the state, including the Delta. It was recently announced that C Spire and Entergy are planning an $11-million fiber infrastructure project that will cover 302 miles in 15 counties in Mississippi.

The project, one of the largest of its kind in the country, was described as “a win-win-win for Entergy, C Spire and the people of rural Mississippi” by Public Service Commission Chairman Brandon Presley.

There is also another broadband access project underway with potential to connect even more remote areas of the Delta and the rest of the country. Efforts are underway to get regulatory approval to use TV “white spaces,” vacant channels that could be used to deliver broadband to rural areas.

Hu Meena, CEO of C Spire, said they applaud any meaningful efforts to provide residents and businesses in rural areas with better broadband and more access.

“While there are still significant hurdles to overcome, we know from experience that a key factor in our success will be how regulators enable and encourage private investment in broadband infrastructure,” Meena said.

Louise farmer Darrington Seward, a member of the Delta Council, recently attended a roundtable discussion with Sen. Roger Wicker to discuss expanding rural broadband service facilitated by Connect Americans Now’s (CAN). Seward is excited about the possibilities.

“As a farmer in the South Delta, I am all too familiar with the challenge of being far from a population center that naturally attracts investment in technology such as broadband access,” Seward said. “Sitting alongside rural advocates and Mississippi business leaders, I heard first-hand stories of challenges our state faces due to lack of high speed internet and the immense opportunities that would stem from better broadband access.”

Farmers have come to rely more and more on broadband access to help them succeed in a challenging farm economy. Equipment has become increasingly sophisticated. Farmers today remotely monitor and manage a lot of equipment. For example, modern precision agriculture involves variable rate applications of fertilizer. Remote sensing equipment connected to farm equipment allows farmers to put just the right amount of nutrients in the right spots, which saves money, improves yields and reduces pollution.

“We can have five or six soil types in any given field,” Seward said. “So, we do soil sampling on 2.5-acre grids. The software we use is all cloud based, and we move a lot of data around.”

Seward is a big fan of CAN’s proposed solution which is to deliver broadband over unused television stations channels below 700 MHz known as “white spaces.”

“You can get a good broadband signal over that and it is pretty low cost,” he said. “You can grow with the times or go down with the ship.”

Seward urges people who favor more broadband coverage in their area to visit ConnectAmericansNow.com to join the CAN coalition today and contact their members of Congress to urge the FCC to take the action to allow the private sector to make this technology available.

Zachery Cikanek, spokesperson for CAN, said this technology makes a lot of sense.

“Right now, 34 million Americans are without reliable broadband service,” Cikanek said. “Of those, 24.4 million live in rural areas where the digital divide is the greatest. A lot of farms, schools and rural clinics are located in an area too remote to bring in the private investment we want to see. With only a handful of potential customers per square mile, telecommunications providers are reluctant to install expensive infrastructure. It can cost $30,000 a mile to lay down fiber optic cable and as much as $1 million to go under a river or lake or through other natural barriers.”

The lack of broadband has consequences.

“Students can’t keep up in many cases with their suburban and urban counterparts,” Cikanek said. “They might have lower math scores, for example. They may go to college less prepared than their urban colleague for careers in the 21st century. Rural clinics pay three times more than their urban counterparts for high speed broadband. If satellite is the only option, you may have limited connectivity, and you are probably paying more for it. It can be even tougher when the only option is to get internet over a telephone line.”

If you are using a modem to dial up for an internet connection, it can be hard to load a single webpage, let alone add an attachment to a simple email. And Cikanek said that can be devastating for small businesses including farmers who want to be able to source more affordable equipment from providers anywhere in the world or who want to access customers outside of the immediate community.

It also has implications for shrinking populations in rural areas if young people leave home to pursue job opportunities at places that have high speed internet connectivity.

Microsoft, a CAN partner, has sponsored pilot programs in more than a half-dozen states using television “white spaces” to successfully connect libraries, farms, schools and students.

Cikanek said if they can get regulatory certainty from FCC that at least three TV “white spaces” are going to remain available on an unlicensed basis for broadband providers, they can quickly bring down the cost of providing the services and aggressively invest in bringing connectivity to these rural communities.

Cikanek said CAN is bringing together rural voices and advocates from all walks of life including experts in telemedicine, remote learning, precision agriculture and economic development who all see broadband connectivity as vital to the future of our rural communities.

“Nearly every facet to our economy is reliant on modern connectivity,” he said. “People are excited about CAN’s plan to close that digital divide in the next five years.”