Takes on Global Challenges at DSU Geospatial Center

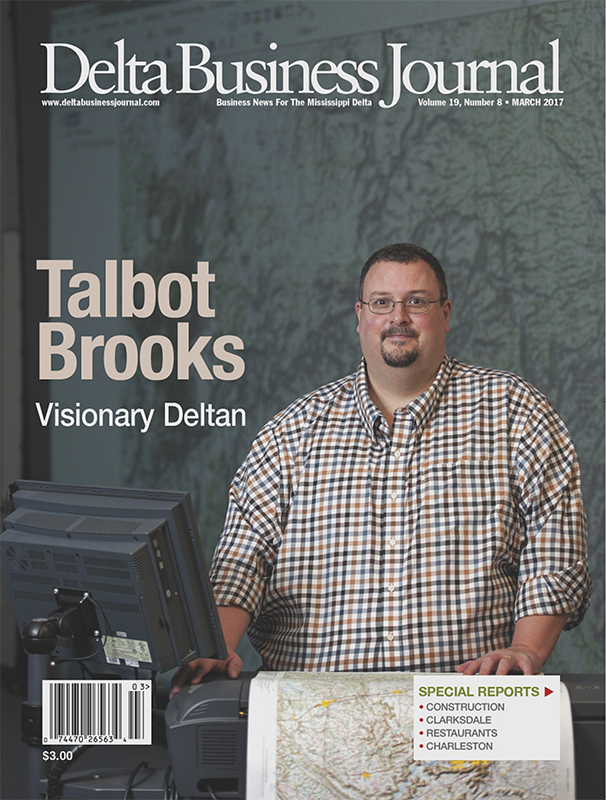

By Becky Gillette • Photography by Rory Doyle

An old saying in real estate is that it is all about “location, location, location.” The same thing might be said about Geospatial Information Technologies (GIT), which use Geographic Information Systems (GIS), Global Positioning Systems (GPS), remote sensing and other techniques to evaluate and solve problems from a geographic perspective.

Talbot Brooks, Director of the Center for Interdisciplinary GIT at Delta State University (DSU), says everything is located somewhere.

“Understanding where and why things are located where they are is critical to unlocking so much about how our world works,” Brooks says. “Everything we do, every day, interacts with geography.”

Few people might suspect the scope of influence for the GIT Center at DSU.

“Our Center is working to insure the safety and integrity of our nation’s infrastructure, safety and defense,” Brooks says. “While there are many applications for farmers, local and state government, and business, our specialty is applying geospatial technologies to defense, homeland security, and emergency management. We really specialize in the application of special technology to assure our nation’s security and defense.”

Take the Koreas as an example. Brooks states that the South Korean and U.S. governments collect satellite, drone or other images that help them understand where the North Korean army is positioned and how it is positioned. Then the military analyzes the information to formulate a battle plan to defend South Korea.

Another example Talbot gives is scanning of millions of acres of empty desert in Afghanistan to find out where the Taliban are training. The same technology can be used to identify the opium poppy fields that are supplying the Taliban with money. Then the military will go and burn those fields.

“About 70 percent of my students are active duty military or working in the intelligence community,” Brooks says. “Our program is 100 percent online from an academic perspective, but from the research and development (R&D) perspective, we do work here on campus. I have hired student workers from the online program to relocate to Cleveland to help us to do some of this R&D work. I have three Marines from Colorado working in my lab right now.’

The GIT in Cleveland is recognized by both the National Geospatial Intelligence Agency (NGA) and the U.S. Geological Survey as a National Center of Academic Excellence in the Geosciences.

“We have the very best of the very best academic and research programs doing this kind of work, and we are partner with NGA in several endeavors,” Brooks says.

Brooks says they like to say that they “fight above their weight class”.

“DSU may be a medium-sized university in rural Mississippi, but we engage in big things and big ideas,” Brooks says. “This takes on many roles like deploying support after a crisis. The center has provided support after more than 60 disasters across the globe. We have also worked with industry giants like Esri to help them integrate the U.S. National Grid into their software.”

Few people might realize the scope of geospatial technology in modern life.

“Our government is founded on geospatial technology,” Brooks says. “Think of how we elect representatives to the U.S. House. The distribution of population determines how many U.S. Representatives each state gets and also determines the number of electoral votes each state gets. We use GIS is how figure that out. You can also use GIT to determine property tax assessments by estimating the square footage of building. It is also used to help forecast the weather. Use of innovative technical approaches offered by GIT helps government agencies, private businesses and non-profit organizations understand problems and make informed decisions.”

Geospatial technologies also have major uses for business planning. By combining a site suitability study with demographic information including age, income and distribution of the population, informed decisions can be made about opening a new business in a particular location.

Another example Brooks gives is if a manufacturer wants to move to Cleveland, geospatial technology can be used to show the available electric, sewer and highways infrastructure, and gives details about the available workforce.

“The same type of intelligence analysis helps a company be more profitable by helping it look inward to make smarter business decisions,” Brooks says. “It can also be used to make smarter decisions about how we govern, and how we manage natural resources. And at the end of the day, that is what this is about: How do you create and use geospatial data to make better-informed business decisions and government policies?”

The GIT Center is a top priority for Mississippi, Brooks says.

While the GIT Center does a lot of work around the country and the world, Brooks states its primary focus is on training students. Students get not only academic instruction, but the opportunity to gain work experience through internships and technical positions in the GIT lab and with their partners. Most students graduate with the equivalent of two years of full-time experience.

Students travel with faculty to observe National Geospatial Advisory Committee meetings, participate in United Nations (UN) technical advisory missions, and present at national conferences.

“Our students have ample opportunity to engage the profession beyond the classroom,” Brooks says. “We excel by combining classroom training with real world experience through cooperative education. They also get educated in a true state-of-the-art facility. The combination of classroom and real-world experiences helps prepare students to advance their careers whether they go to work for governmental agencies, non-profits, private businesses or academia.”

Another bonus is help getting out of college without owing a large amount for student loans. Brooks says they help students finance their education by providing scholarships and paid internships that help nearly all of their students.

Students are required to work in the field prior to graduation. That also helps with their job prospects after graduation. For some, their cooperative work experience might lead to a job offer after graduation. Brooks says students have found work with local and state governments, the National Geospatial Intelligence Agency, the U.S. Marine Corps, Mississippi Emergency Management Agency, large private sector firms like Lockheed-Martin and Sanborne, and other government agencies.

The future is bright in a field that is considered one of the ten fastest growing fields for employment in the country. And prospects for good pay are also good.

“The average starting salaries are in the mid-30s,” Brooks says. “After three years, salaries are in the mid-50s. After five years, salaries are usually in excess of $60,000, but salaries in excess of $120,000 are not uncommon.”

Students are also encouraged to be innovative and resourceful thinking ahead to the next big game changer.

“Our center is committed to thought leadership,” Talbot says. “Our faculty have significant industry experience, play national and global leadership roles in the geospatial industry, and are recognized innovators. Moreover, we work to actively shape the discipline through professional societies and organizations.”

Brooks has been interested in maps since he was a young boy.

“My grandfather was a retired captain of a Navy destroyer and used to take me out with my uncle on his boat on the Long Island Sound,” Brooks says. “My grandfather taught me to navigate and I’ve been hooked on maps ever since.”

Brooks did undergraduate work at the Rochester Institute of Technology and received master’s degrees from Arizona State University in plant biology and biology\pre-medicine. In 2016, he became one of the first six people in the country to earn a Universal GEOINT Professional (UGP) certification from the U.S. Geospatial Intelligence Foundation.

Brooks spends a lot time traveling. A snapshot of his working life is a recent trip where he first traveled to Maryland to teach fire chiefs at the U.S. National Fire Academy how to use geospatial technology to keep their communities safe. Then he went to Washington D.C. to meet with colleagues from the NGA to discuss some projects his Center is working on for them. That was followed by attending a meeting of the U.S. Geospatial Intelligence Foundation where he is chair of the Certification Governance Board. That is the organizations that maintains professional credentials for the industry. Brooks says it is the equivalent of taking the bar exam to be certified to work in the geospatial industry.

Later this year he will travel to Southeast Asia to work with the UN.

“I serve as a U.S. technical advisor to developing nations, teaching and helping them learn how to use geospatial technologies to better plan for and respond to disasters.”

For Brooks, there is no bright line between work and play.

“It is hard to separate my personal life from my professional life,” Brooks says. “I don’t think I’ve ever ‘worked’ a day in my life. My wife, Darlene Brooks, would probably agree. As far as hobbies, I am quite passionate about photography. And, of course, that is closely related to satellite imagery and aerial photography. I was a volunteer firefighter until recently. I did that for 31 years. And my wife and I rescue boxer dogs.”

For more information, see the website http://www.deltastate.edu/artsandsciences/geospatial-information-technologies/, send an email to tbrooks@deltastate.edu or cdsmith@deltastate.edu or call 662-846-4520 or 662-846-4521.