2nd Chance Program Helps Adults Succeed in Education and Workforce Training

By Becky Gillette • Photography by Timothy Ivy

It could have been tempting after Richard “Dickie” Scruggs got released from federal prison in 2013 after serving six years on charges related to judicial bribery to have relocated to another state rather than come back home to Mississippi. But Scruggs bet on the people in Mississippi being willing to give him a second chance and hasn’t been disappointed. And now he, his wife, Diane, and their son, Zachary, fund and operate a program called 2nd Chance that has helped about 1,110 people in Mississippi overcome barriers to earning a high school equivalency degree and\or (and\or) a workforce training certification.

JoAnn Tisdale, college and career navigator, Mississippi Delta Community College, says 2nd Chance helps students with critical needs such as transportation, tuition fees or child care that might prevent them from getting credentials that will help them rise up out of poverty.

“We have so many people who have just been kicked down,” says Tisdale. “We want to give them an opportunity to better themselves and make a future for themselves and their families. 2nd Chance has been there for those students to jump those barriers that kept them from finishing school. It is very rewarding to see them be successful. When they are able to be successful, they take pride in themselves and you can see it in their attitude, the way they dress, and the way they perform.”

The students in adult ed typically don’t have a support system, said Laurie Kesler, director of adult education, Northeast Mississippi Community College. 2nd Chance steps in to fill gaps.

“2nd Chance is a resource we can use to help pay tuition, electric bills, gas for their vehicle or anything else that keeps them from completing their education,” says Kesler. “In many cases, if 2nd Chance didn’t step in, they wouldn’t be able to finish workforce training, a college degree or high school equivalency diploma. 2nd Chance is willing to help in all aspects that are needed.”

Dickie Scruggs was considered one of the best trial lawyers in the U.S. after he was successful in leading lawsuits by Mississippi and 30 other states against the tobacco companies in the U.S. for covering up knowledge of the addictive nature of tobacco and its negative health consequences. In 1999 there was a fictionalized account of the case produced in an Academy Award-nominated movie called The Insider staring Al Pacino and Russell Crowe.

Scruggs got the confidence to take on Big Tobacco after success with representing thousands of shipyard workers exposed to asbestos, which can cause serious lung diseases. His Pascagoula firm that opened in 1980 at one point had sixty-five employees handling the litigation against the asbestos companies that ran from the mid-1980s into the 1990s.

“I didn’t have to be educated about the working conditions at the shipyard because I worked there during college for two and a half months each summer,” says Scruggs, raised by a single mother who worked as a secretary at Ingalls Shipbuilding. “I didn’t get ill, but I appreciated the conditions these people had to work under and it gave me special empathy for their plight. It was a challenge because there were a lot of companies that made those products, and they all collaborated to defend themselves. It was a monolithic group of top lawyers. It was a real intellectual and professional challenge to go toe-to-toe with them.”

The main defense of the asbestos companies was that many shipyard workers also smoked.

2nd Chance MS Team (from left); Dickie Scruggs, Catti Beals, Director of Development, Sarah Rose Lomenick, Director of Programs and Zach Scruggs

Zach Scruggs speaking at the 2nd Chance MS’s 2021 Fall Fundraiser held in Oxford on October 7.

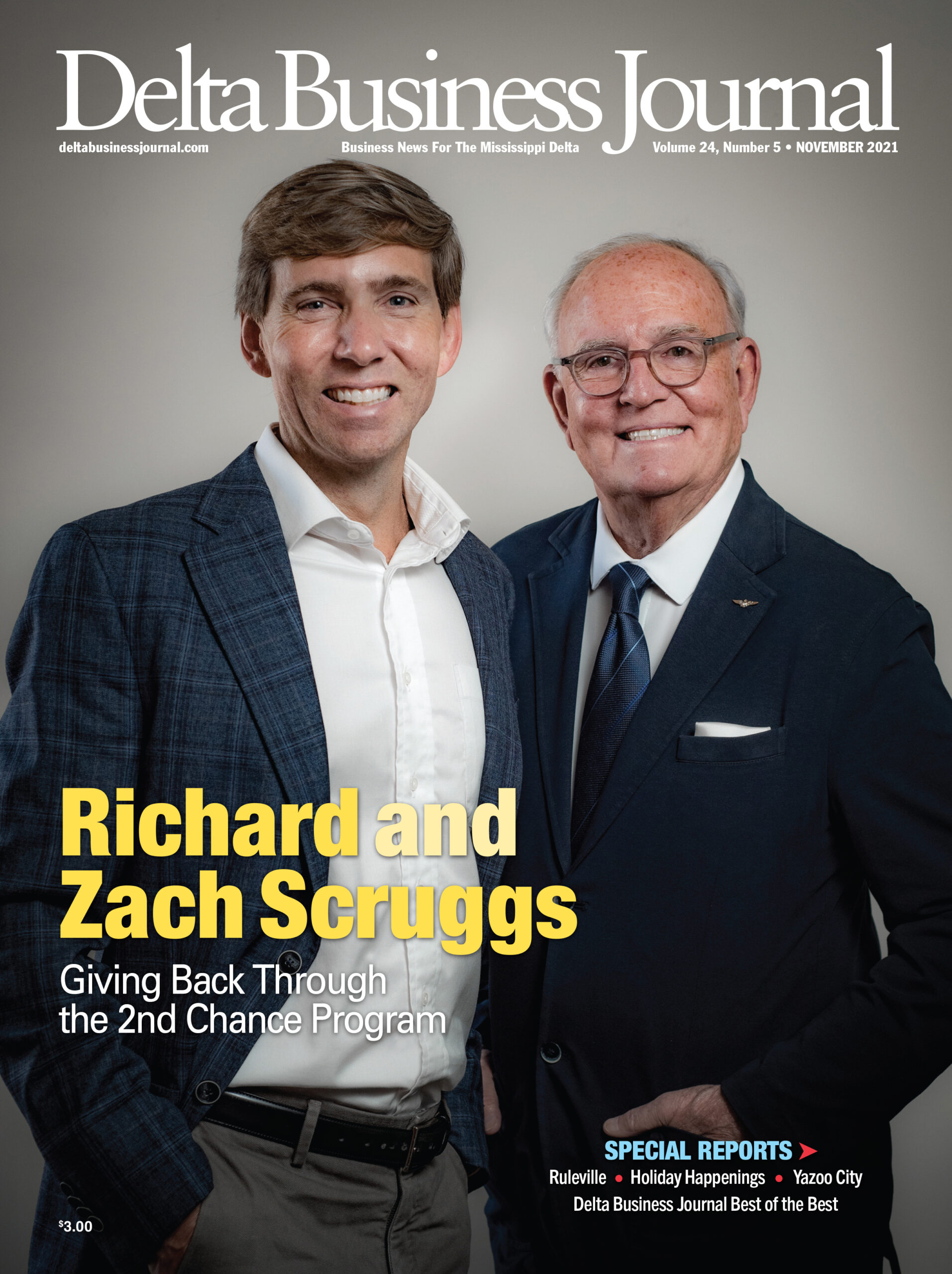

Richard and Zach Scruggs overcame unfortunate life events and parlayed their experiences into a successful venture which has helped hundreds of deserving Mississipians reach their full potential.

The 2nd Chance Program has helped over 1,110 people in Mississippi overcome barriers to earn their high school equalivalency degree and/or workforce training certification.

“The asbestos companies pointed the finger at the cigarette industry even though it was a very different kind of lung disease than caused by smoking,” says Scruggs. “We lawyers had to learn a lot of pulmonary medicine. We made a lot of money in attorney fees with the asbestos lawsuits which we were able to reinvest into the tobacco litigation. The knowledge or the science of lung disease was very helpful, too. In a lot of ways, the asbestos companies made our case against the tobacco companies. No one had ever won against tobacco at that point. It had the feel at the time like suing energy companies today for global warming. It seemed like it was far-fetched litigation. Lawyers, who by and large work on a contingency fee basis, weren’t that interested in suing Big Tobacco.”

But with a good war chest from asbestos litigation, Scruggs was able to get other law firms to join without a big financial obligation. They started out just suing in Mississippi, West Virginia, Florida and Minnesota. The case started getting traction when they developed a whistleblower who got on 60 Minutes.

“We picked up more and more states,” says Scruggs, a former Navy carrier pilot who received his undergraduate and law degrees at the University of Mississippi. “Finally, one company settled with us, and that brought in about fifteen more states because it was the first time a tobacco company had settled. Ultimately, we represented thirty-one states and a couple of territories. The 1997-1998 settlement in all the states in the country was valued at about $250 billion. It was by far the biggest legal achievement of my career, no question.”

Scruggs felt invincible.

“The insane amount of money I made meant I could have easily retired, but that felt sacrilegious at the time,” says Scruggs. “I took on several issues, but nothing of the magnitude of my earlier work. Then there was an attorney’s fee dispute that developed out of representing homeowners following Hurricane Katrina. The judge in the case asked for money. Stupidly, I agreed to pay him. It was a set up to get me. I was too big for my britches. It was a sobering experience, to say the least. I got charged and pleaded guilty to mail fraud. I was sentenced to federal prison for seven years and I served six years.”

It was a hard landing for someone who was an avid sailor who raced frequently including in the America’s Cup in New Zealand. He was sixty-one when he went to prison, and his first year was in a low-security prison in Kentucky that was pretty restrictive. His last five years were in minimum-security prison camps including his last three years at a facility in Montgomery, Ala. His wife, Diane, came to visit every single weekend when he was away.

While being imprisoned wasn’t fun, he says it wasn’t dangerous or draconian either. In federal prison, education is provided by inmates with the prison staff supervising.

“I taught math preparing inmates to take the math section of high school equivalency exams,” says Scruggs. “I had to go back and learn some things to teach it. The math section of the high school equivalency exam was pretty hard. I don’t know many people who could walk right in and pass it no matter their background. It was the hardest part of the test. Most people who drop out of high school do it in the ninth grade when they hit algebra.”

Scruggs said his motivation for teaching was to help inmates have a future when they got out of prison.

“It gave me a new sense of purpose in prison, a reason to get up every day,” says Scruggs. “I was as much a cheerleader as I was a teacher.”

After he was released, in 2014 he heard an interview on Mississippi Public Radio with a woman from Hinds Community College talking about the difficulties of getting people to pass all five parts of the high school equivalency exam before the protocols changed at the end of the year.

“I called and volunteered to be a tutor,” says Scruggs. “She called me back and asked me to come down and meet with her and Dr. Clyde Muse, the president of Hinds Community College. Dr. Muse encouraged me to set up the program that became 2nd Chance. I spent a year going around to different community colleges talking to adult ed people. We started collaborating with community colleges around the state providing sponsorships for students to pay tuition, twenty dollars a week for satisfactory attendance, and a small cash bonus of $250 when they graduated. As the years have progressed, we have gone beyond supporting high school equivalency diplomas and put a lot of emphasis on career readiness certification and workforce training.

“2nd Chance is the major project in my life now. We have now helped about 1,100 young adults in some form or fashion with diploma or workplace certification. For about $500, a student can get some kind of credential to help them get a better job. We are in twelve of fifteen community colleges in the state.”

The Scruggs take no salaries for 2nd Chance, and are the primary funders of the program. They recently held their annual fundraiser again after being unable to do it for eighteen months because of Covid.

Scruggs has been approached by several organizations to get involved in an inmate reentry program. But they want to do more than be a Band-Aid.

“In federal prison, you have to sit in a class until you pass a high school equivalency degree,” he says. “But there are no meaningful educational offerings or job trainings in state prisons. Until the state gets serious about doing that, I don’t know if we can help.”

Zach Scruggs is the executive director for 2nd Chance. He followed in his father’s footsteps and attended Ole Miss for undergraduate and law school degrees. Then, worked for his dad and went to prison for fourteen months on a charge of failure to report a lesser felony in the judicial bribery case. Scruggs was also involved in teaching in prison.

Unable to practice law again, the younger Scruggs moved to Florida where he worked for a solar and energy development company for four years.

“It was good after all that happened to get out of Mississippi for a while,” says Zach. “And I enjoyed my opportunity there to work in alternative energy development. I was content doing that.”

Zach learned that a lot of students are “one flat tire” away from dropping out good. Initially, he declined his father’s offer to run the organization.

“As it started gaining speed, I got the call again,” says Zach. “My father said, ‘This thing is really taking off and I need someone to come run it. We want a proper, certified 501(c)(3) non-profit with an executive director. If you don’t do it, I’ll have to hire someone.”

The Scruggs were attracted by the idea of not just helping people, but state businesses and industry and the economy as a whole. The younger Scruggs took off running, got it certified as a non-profit public charity, and then put a laser focus on developing programs with community colleges to get more adults in these programs and keep them in.

“The community colleges offer a plethora of workforce training courses running six weeks to a semester that cost $250 to $1,000,” says Zach. “That might as well be $10,000 to the population we are talking about. A key barrier needed to be removed to allow people to come out of one of these workforce programs and can get a job right away. Give them an employable certificate. Advanced manufacturing is particularly in demand, as are jobs as a Certified Nursing Assistant, a pharmacy tech, a commercial a truck driver, and a utility lineman. These community colleges tailor their programs to what industry wants.”

Mississippi has one of the top ranked community college systems in the country.

“It is a hidden asset that we are trying to use to fix some of the issues that are keeping us behind in Mississippi,” says Zach. “Mississippi has the highest number of high school dropouts and the second lowest workforce participation rate in the country. There is a fix to that. The community colleges can solve both those issues.”

Since COVID-19, technological assistance became a big deal because a lot of education went virtual. 2nd Chance started a program to check out MacBooks to students and help them get access to the internet.

“We remove whatever barrier can be reasonably removed, and are 100 percent dependent on community college partners,” says Zach. “We don’t screen the students. They do that. They have our funds available and they know the adults who need help. The adult ed instructors are like missionaries. They are really a godsend dedicated to helping their students succeed.”

The amount of assistance to each student averages between $500 and $1,000.

“A little bit goes a long way,” says Zach. “We hope this is a model that other charitable groups and the government can use. When people are more employable, it helps their family and they are less likely to need public assistance. The collateral consequences that flow from adult education all make sense. The compounding affects more than the actual student. It impacts the family and society as a whole.”